The Heifetz War Years

By John and John Anthony Maltese

In a U.S. Army hospital in Italy, a violinist dressed in military uniform entered a ward to play for GI’s wounded in the ongoing battles of World War II. The ward was for young men who had recently lost arms and legs under fire. As the violinist entered, a boy who had lost his right arm tried to applaud in the air with his left hand. The violinist was momentarily shocked. He had played in many hospitals before, but none quite like this. He gazed at the smiling boy clapping the air, and then – his face illuminated with compassion and sensitivity – raised his violin and played. The violinist’s name: Jascha Heifetz.

Seated next to Heifetz at the “GI Steinway” was pianist Milton Kaye. Kaye never forgot that concert. “Here was this man,” he recalled fifty years later, “the great violinist of the ages, and he was killing himself to play even better for these men! And I thought to myself, ‘You see, sonny boy? That’s why he is what he is.”[1] Kaye had never, ever, heard Heifetz play so beautifully. The following year, the pianist Seymour Lipkin witnessed that same high standard of violin playing when he accompanied Heifetz on another tour for the GI’s. Not even the most adverse conditions affected Heifetz’s playing. “I remember that after awhile I began to understand that he was going to play his best no matter what,” Lipkin told us. “And I kind of perked up, and I thought, ‘Boy, this is something!’ He played at his best no matter what. So, I tell my pupils now: ‘Don’t forget that. That’s a lesson!”

Heifetz had been so moved by his concert for the paraplegics that he asked to play at more hospitals. He wanted to use his days off as the opportunity for the additional concerts. Heifetz asked Kaye if he minded adding more concerts to their already grueling schedule. “Of course not,” he shot back. Kaye, too, had been moved. He had fought back tears as they played in the hospital. Besides, he considered every opportunity to play with Heifetz a unique privilege. “And it was,” Kaye told us as he leaned forward in his chair. “It was the greatest privilege I had in my musical life.”

The concerts with Milton Kaye came in June 1944, during the second of Heifetz’s three international tours for the USO during World War II. His efforts during the war tell the story of Heifetz’s strong patriotism – a story that helps to reveal a deeply personal side of this intensely private man. This is that story.

As Kaye reminded us, Heifetz was not born in the United States: “He became an American citizen, and he said, ‘I’m going to do something for the country I have adopted.’” Born in the town of Vilnius in Russian Lithuania on February 2, 1901, Heifetz had come to the United States as a boy of sixteen. Becoming a naturalized U.S. citizen in May 1925 was a great milestone for Heifetz, and he remained passionately patriotic until his death in 1987. Ayke Agus, Heifetz’s student and confidante during the last years of his life, wrote about the great pride that he took in his U.S. citizenship. She witnessed that pride first-hand at Heifetz’s California beach house in Malibu. “On national holidays he was among the few in Malibu who always raised the flag in the morning,” she wrote, “and he took it down himself at sunset. He rigorously required all guests to be present at the ceremony and to display the proper respect toward the flag while it was lowered.”

She added that Heifetz took particular pride in knowing precisely how to handle the American flag. “If his students were present at the beach, he never missed the opportunity to teach them how to fold the flag properly and how to store it in its box.” When the gilded sphere at the top of his tall flagpole showed signs of wear, he went to great expense to have it not just polished, but plated in gold. He asked Agus to help him. “Finding a company that would accept the job of gold plating it as Heifetz wished, instead of just adding gold leaf, was difficult,” she wrote. But Heifetz got what he wanted, and his flag flew with renewed luster.[2]

Not surprisingly, Heifetz was eager to offer his services during World War II. Even before U.S. entry into the war, he had volunteered for various assignments in the Civilian Defense Program and had been active in fundraising. At one memorable concert at the Copa Club in Beverly Hills in August 1941, Heifetz joined forces with Arthur Rubinstein, Bruno Walter, and Lotte Lehman in a benefit concert that raised $10,499 for British War Relief. Lord Halifax wrote that the generosity of Heifetz and the other musicians was “yet one more proof of how artists in free countries have rallied to the succour and help of British men, women, and children who are defending the cause of freedom on the front line.”

Two months later, Heifetz spoke to a nationwide radio audience in the United States as part of a program supporting the Treasury Department’s sale of Defense Bonds. “My strong feeling for this country makes me very proud to appear on this program,” he said. “Just as it is difficult for a fellow to be a hero in his own home town – so, perhaps, it takes a naturalized American, like myself, to fully realize what a very great country this is.”[3]

Like all Americans, Heifetz was shocked by the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. Now he was more eager than ever to make himself useful in every way possible. Within weeks, that included giving his first stateside USO Camp Concert. The experience was a new one for Heifetz. Not only was he playing for an audience that did not necessarily like classical music, but USO officials told him just before he walked onstage that he should talk to the soldiers.

“I learned backstage that I had to be my own musical commentator and play besides,” he later recalled. Violin playing was easy, but talking in public was difficult for the shy and reticent Heifetz. Unsure of what to say, and uneasy about how he would be received, he walked out onstage. “Before me were hundreds of eager faces,” he said. “I was more nervous than in all my past career.” He paused for a minute and looked at the soldiers. Finally he said, “I don’t know whether you will like this or not, but you are going to get some Bach just the same.” He played and when he finished there was enthusiastic applause and shouts for more. More at ease, Heifetz went on: introducing them to Beethoven, Brahms, and Tchaikovsky.[4] As he played and talked, he created the format that he would use in more than 300 USO concerts to come.

Over the next three years Heifetz not only gave many stateside USO Camp Concerts, but participated in three USO tours outside of the United States — playing for troops in Central and South America in 1943, North Africa and Italy in 1944, and England, France, and Germany in 1945. To his surprise, he was a hit with the soldiers. They even demanded that he make several appearances on “Command Performance,” a radio request show where soldiers chose the stars and determined what they would perform. When asked by the GI’s, Heifetz would do almost anything, including a comedy skit and duet with the comedian Jack Benny in 1942. His deadpan delivery played perfectly off of Benny. After the comedian improvised a wretched cadenza in the middle of their duet rendition of MacDowell’s To a Wild Rose, he proudly turned and asked, “How was that, Mr. Heifetz?” With perfect timing, Heifetz skipped a beat and replied politely: “Shall we continue, Mr. Benny?”

For years, Benny tried to convince Heifetz to repeat the skit they had done together on “Command Performance” for his commercial radio show. Whenever Benny brought it up, Heifetz’s simple reply was: “Only for the troops.” Another “only for the troops” rendition on “Command Performance” was of the title song from the United Artists motion picture “Intermezzo,” which had starred Ingrid Bergman and Leslie Howard. Heifetz introduced the piece himself, saying: “There have been several requests for the next number so, whether I like it or not, I shall play for you Intermezzo.” He proceeded to play it brilliantly.

Heifetz’s radio performances, including his many appearances on NBC’s “Bell Telephone Hour,” were rebroadcast to the troops over the Armed Forces Radio network – often as part of the “Concert Hall” program hosted by actor Lionel Barrymore. And, when NBC radio highlighted the “Soldiers in Greasepaint” who were performing for troops around the world, Heifetz was the only classical musician featured alongside Bob Hope, Bing Crosby, and the other popular entertainers of the day. He appeared on the program with Emanuel Bay in a shortwave radio transmission from Panama where they were playing for troops as part of an extended USO tour.

The Pan American tour was Heifetz’s first USO tour outside the United States and it was Bay’s last. The heat was oppressive and the upright piano that they carried with them from performance to performance was so often out of tune that Heifetz frequently had to play unaccompanied. The tour, which spanned the Fall of 1943 and the Winter of 1944, took them through the Panama Canal Zone, and to Nicaragua, Ecuador, Honduras, Peru, and even the Galapagos Islands.

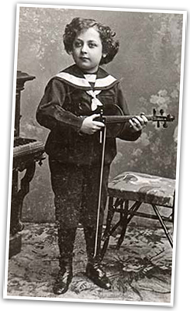

Bay evidently found the experience grueling, and when Heifetz announced that he had signed up for another USO tour in June and July of 1944 – their vacation period – Bay did not want to go. That decision created a rift that threatened their long-standing relationship. Bay had served as Heifetz’s full-time accompanist since 1935, but their partnership went back far further than that. They had met at the St. Petersburg Conservatory in Russia when they were both students. In fact, Bay had accompanied Heifetz at his very first appearance in a group recital there on November 5, 1910, and again for Heifetz’s first full-scale recital in the conservatory’s small Maly Hall on April 17, 1911.

Now that Bay refused to go on another USO tour, Heifetz had to find a new accompanist. In New York, Milton Kaye had recently been deferred from military service. He was just at the cusp of being too old to serve, and he was the sole means of support for his parents and his recently divorced sister and her child. Still, he wanted to do something for his country, so he went to the USO office to volunteer as a pianist. “Give me the first opening you have,” he told them. “It can be part of a jazz band, anything.”

In the meantime, Heifetz in California asked his violinist friend Sascha Jacobson if he knew of an accompanist who would travel with him on such short notice for the USO tour. Jacobson telephoned Paul Bernard, the second violinist in his Musical Arts String Quartet, to ask his advice. Bernard was in New York where he worked at the classical music radio station WOR with Kaye. Kaye had performed regularly on WOR since 1932, playing everything from piano concertos to accompaniments for other musicians on frequent live radio broadcasts. Bernard thought highly of Kaye and recommended him. As a student at the Juilliard School, Kaye had accompanied some of Jacobsen’s students. Now that Bernard suggested him, Jacobsen remembered Kaye. Both agreed that Kaye would be a good choice for Heifetz.

Bernard quickly found Kaye and said, “Hey, I just heard that Jascha is looking for a pianist.” “Jascha who?” Kaye asked. “What do you mean Jascha who,” Bernard shot back, “there’s only one Jascha. HEIFETZ!” Kaye was stunned. The chance to play with Heifetz was the last thing he ever expected. And the timing was perfect – he had just signed up as a pianist for the USO. So Bernard arranged for Heifetz to telephone Kaye. It was set for 8:00 p.m. the next evening, and Bernard warned Kaye to be waiting by the phone. Heifetz would call only once. The call came at precisely 8 o’clock. “Sascha Jacobson and Paul Bernard both think highly of you,” Heifetz told him. “I will be in New York soon and, if you are interested, perhaps I could hear you play.” With his heart racing, Kaye managed to reply: “It would be a privilege.”

The audition took place at Heifetz’s suite at 5th Avenue and 59th Street. Heifetz led him to the piano, which was stacked with music. To Kaye, it looked like there must be 300 pieces there. Heifetz took the top piece off the stack, the Londonderry Air (“Danny Boy”) and put it on the piano rack. Kaye glanced over it, took a deep breath, and launched into the introduction, but when the violin was supposed to enter there was silence. Kaye froze. Why wasn’t Heifetz playing? But Heifetz said, “Go on, go on!” Kaye realized that Heifetz wanted to see how he would play the accompaniment without him. So he tried to guess how Heifetz would play. He sensed Heifetz’s approval. After letting Kaye play the entire piano part alone, Heifetz said, “Alright. Now, let’s start again.” This time Heifetz played along, but he was still testing Kaye. He played with exaggerated and unpredictable rubato as if to say, “Follow me, if you can!” As it turned out, Kaye could. His years of experience on the radio playing with unpredictable musicians on short notice had served him well. Heifetz seemed pleased.

One by one, they proceeded to read through the stack of music on the piano. As they did so, Kaye noticed that Heifetz had carefully marked every piano part. The smallest diminuendos, crescendos, and accelerandos were penciled in. Heifetz had even written in the fingerings that he wanted the pianist to use. They played for hours. When they got through the stack, it was dark outside and Heifetz had himself a pianist. Before Kaye left that day, Heifetz warned that he expected only the best from him. “If you are an artist, you do things correctly,” Heifetz explained. “Not half way – fully.” He paused and looked at Kaye. “Do you want to be an artist?” he asked. Kaye nodded. “Then no approximation,” Heifetz said. The blood must have drained from Kaye’s face, because Heifetz then offered some revealing words of comfort: “If you think I am tough on you, remember, I am twice as tough on myself.”

With that, their first meeting was over. It was also their only rehearsal before the tour. Heifetz had warned Kaye to be prepared to play any of the compositions from the stack that they had read through, but Heifetz did not seem worried. He could tell from the audition that he had found a good pianist. In the coming days, Kaye prepared for the tour. Neither Heifetz nor Kaye was told where they would be sent, or even precisely when they would be going. An army official told Kaye that when the time came, he would get a phone call saying simply: “Your aunt would like to hear from you.” Upon receiving that call, he should go to Number 1 Park Avenue South, the embarkation point from New York, and await further instructions. Kaye said it was like being cast as a character in a spy movie.

The telephone call finally came. Kaye took a cab from his home in Flushing to the embarkation point where he met Heifetz. A military escort took them to an airfield. Kaye had never been in an airplane, and he was none too happy about the prospect of flying. Their escort dropped them off by a four engine supply plane. They climbed aboard, and found themselves in what amounted to a cargo hold. All the seats had been taken out, and they were surrounded by crates of machinery and foodstuff. Three other men were flying with them. Kaye’s first thought was, “There’s no place to sit!” This clearly would not be first class travel. The military treated Heifetz and Kaye just like any other soldier. They would sit on a crate.

Once in the air, Kaye’s unease about flying turned to terror when Heifetz suddenly pronounced, “I don’t like the way the engine sounds.” Kaye was stunned. Heifetz had one of the most attuned set of ears in the world, he had flown around the world countless times, and he didn’t like the way the engine sounds? When they proceeded to make an unexpected landing, Heifetz seemed more satisfied than scared. His ears hadn’t let him down. “I knew there was something wrong with the engine,” he said proudly.

Eventually they took off again. It was clear that they were crossing the Atlantic, but they still had not been told precisely where they were going. The weather was stormy, the flight turbulent, and the cargo hold was cold. This was not what Kaye had imagined a concert tour with Jascha Heifetz would be like. When they finally descended from the clouds, all the passengers were peering out the window. Perhaps a landmark would tip them off to where they were. To Kaye, it looked like they were landing on a different planet. Heifetz stepped back from the window. “Casablanca,” he said.

Casablanca sits on the northwest coast of Morocco, almost due south of Portugal and not far from the Strait of Gibraltar. U.S. forces, under the direction of General George S. Patton, Jr., had invaded Morocco near Casablanca on November 8, 1942. Morocco was then controlled by Vichy France. The U.S. landing took place just four days after British Eighth Army troops, led by Lieutenant General Bernard Law Montgomery, had defeated Field Marshall Erwin Rommel’s German Panzer division at El Alamein, Egypt, hundreds of miles to the east. As U.S. forces landed near Casablanca, British troops landed in between Morocco and Egypt in Algeria, near the cities of Oran and Algiers. The campaign marked a turning point in the battle to control North Africa. The squeeze forced German troops to retreat to Tunisia, just off the coast of Sicily, where 275,000 German and Italian troops surrendered on May 12, 1943.

With Allied forces on the offensive, Major General Omar Bradley assumed control of the U.S. II Corps in North Africa, and General Patton took over the planning for the invasion of Sicily, which took place on July 10, 1943. The Allies won control of Sicily on August 17, paving the way for the British Eighth Army to land on the toe of the Italian boot on September 3, with the U.S. Fifth Army following six days later. The campaign would be a long and hard one. Although Rome fell to the Allies on June 4, 1944, just as Heifetz and Kaye began their USO tour, fighting raged on in northern Italy where German forces did not surrender until almost a year later: on May 2, 1945.

Heifetz’s USO tour followed the route that Allied forces had taken. He and Kaye gave their first concerts in Casablanca, and then flew east to Oran and Algiers, up to the island of Sardinia, over to Sicily, and then across to Italy, playing concerts everywhere they went. Their days took on a regular pattern. A jeep would pick them up around nine o’clock in the morning for their first concert of the day. Each concert lasted between 45 minutes and an hour. They always began with Bach (“Think of it as your musical spinach,” Heifetz would joke, “you may not like it but it’s good for you”), and always ended with Heifetz’s arrangement of Dinicu’s Hora Staccato (or, as he was calling it by the end of the tour, that “horrible staccato”). What came in between depended on Heifetz’s mood and the soldiers’ attentiveness. The best audiences would get an entire violin concerto or a complete sonata. Average audiences would get a movement or two of something more catchy, like Lalo’s Symphonie Espagnole. The most inattentive audiences got just short pieces.

Quite apart from the attentiveness of the audience, Heifetz preferred to vary his programs. Except for the opening Bach, the closing Hora Staccato, and a few pieces that the soldiers invariably requested (such as Schubert’s Ave Maria), the bulk of the concert almost always changed. When Heifetz returned from his USO tour of England, France, and Germany the next year, he boasted that he had played 65 concerts and never repeated a composition except by request. The troops, though, had asked him to play that “Horrible Staccato” at 63 of the 65 concerts, and Heifetz complied.[5]

After the first concert of the day, Heifetz and Kaye would mingle with the troops, sign autographs, and then get back in the jeep and drive to another concert. Often they gave four concerts a day. Kaye was always amazed that Heifetz never ate until after the last concert. “Me, I’d have breakfast,” Kaye said, “but he wouldn’t eat anything. Maybe a sip of coffee, but that was it!” At the end of the day they would return to their base. Although he always received invitations to dine at the Officers’ Club, Heifetz usually refused. He preferred to eat with the enlisted men. “I like to be with the ordinary soldiers,” he told Kaye. “They’re more fun than the officers.” Besides, he added, “They play better ping-pong!”

One reporter in Algiers got wind that Heifetz had turned down dinner invitations from both the Army and Navy officers’ clubs, and went in search of the violinist. He found him at an enlisted men’s canteen “munching sandwiches and swapping gossip with G.I.’s on their musical likes and dislikes.”[6] After eating and having one drink, Heifetz would sit down at the piano and play some jazz for the soldiers. “He was an excellent pianist,” Kaye recalled. “An excellent pianist! And then we’d play four-hand jazz. And then he’d say to me, ‘You play some things.’” When he could, Heifetz would also play ping-pong with the soldiers. If there was no piano or ping-pong table to be found, he would just “hang around and laugh with the enlisted men.” Then he would go to bed and repeat the whole routine the next day.

Concerts were often improvised as the tour progressed. Some were for small groups of soldiers, with Heifetz and Kaye playing in the back of a flatbed truck. Others were concerts for thousands of soldiers. Days off were scheduled, but Heifetz seldom took them. Kaye’s diary entry for June 19 serves as one example:

“Supposed to be day off. Heifetz decided to put in another hospital in the afternoon. Planned an outdoor concert, [but] rain drove us into a big tent. 300 loud speakers connected into wards. About 2000 beds in place. Went well. Heifetz is superb in conditions like these.”

On another scheduled day off, Heifetz wanted to play a concert for a small troop of Palestinian Jews, so he and Kaye arranged for pilot to fly them to the troops in a twin-engine plane. The concert, for about 60 men, was a huge success. The commanding officer was so thrilled that he invited Heifetz and Kaye to his quarters after the concert, proudly pulled out a bottle of Haig & Haig Scotch whiskey, and offered everyone a drink. “Heifetz knew that this was a month’s ration,” Kaye recalled, “so he said, ‘No, I don’t want a drink.’” To that the commander replied, “Gentlemen, either I break this bottle on the floor or we drink it! Which do you want?” The pilot who had flown Heifetz and Kaye to the concert was with them, and he seemed especially eager to partake in the alcohol. Heifetz and Kaye both enjoyed a couple of drinks, but the pilot did his best to finish off the bottle. By the time they were ready to fly home, the pilot was drunk. “Now that trip home,” Kaye said with laugh, “even Heifetz turned pale. It was loop the loops all the way!”

Rather than bringing his priceless Guarnerius or Strad on the tour, Heifetz used the 1736 Carlo Tononi violin that he had played at his 1917 Carnegie Hall debut. His family had bought the violin from the renowned dealer Emil Hermann in the summer of 1914 when the 12-year-old Heifetz was studying with Leopold Auer in Germany. “He chose a violin by Carlo Tononi of Bologna from my collection,” Hermann later explained, “but he couldn’t afford to pay for it. I was so impressed with his genius that I agreed to sell it to him for much less than it cost me, and I allowed him to take it with him to Russia. I told him that I would gladly wait for payment until he was able to settle.”[7] Heifetz remained fond of the Tononi throughout his life, and used it for his last two public concerts at the University of Southern California in the early 1970s. Like bookends, the violin opened and closed his American career. In 1944, Heifetz still used gut D and A strings. In order to have fresh, unfrayed strings, Heifetz changed them every few days (the A somewhat more frequently than the D). Milton Kaye observed with amazement that Heifetz used an exact replica of the Tononi made by the maker Carlyle to stretch the fresh gut strings before putting them on the Tononi.

Heifetz and Kaye worked their way north from Sicily up the west coast of Italy. In northern Italy, Heifetz and Kaye came face to face with the war. Shortly after their arrival, they were driving near the war zone and witnessed a mid-air collision between two planes. One of the pilots ejected before impact, but his parachute did not open. Heifetz and Kaye watched in terror as he fell to the earth. They stopped their jeep and ran up the hill where they found the body. Their driver took the pilot’s dog tags and covered the body with the chute that had failed to open. As they walked through the woods they found an engine from one of the planes and then the fuselage, along with the body parts of another pilot. It was an encounter Kaye never forgot.

Many of their concerts in northern Italy were given under dangerous conditions. A flatbed truck carried an upright piano into battle zones, with Heifetz and Kaye traveling along by jeep. One of the most harrowing experiences came on June 16. They had traveled for two hours over war torn roads through dizzying mountain passes. When they finally arrived at their destination, they could hear the sound of guns booming in the distance. They climbed into the back of the truck to play for a group of soldiers. The piano – painted olive-drab to camouflage it – was dusty and had been knocked out of tune by the journey, but Heifetz played as if they were on the stage of Carnegie Hall.

They made it through the Saint-Saëns Introduction and Rondo Capriccioso and had just begun Schubert’s Ave Maria when suddenly they heard the roar of approaching aircraft. “German attack!” shouted one of the soldiers. The gun crews ran to their posts, and the rest of the soldiers scattered. Heifetz and Kaye looked at each other. They didn’t know where to seek shelter, so they jumped off the truck and took cover under a tree. “Under a tree,” Kaye exclaimed as he recounted the story to us, “as if that would have done any good.” There, with rounds of anti-aircraft fire going off around them, Heifetz still held his violin. “I just stood there, watching the show,” Heifetz later recalled.

Suddenly a young soldier ran toward them, knocked Kaye out of the way, snatched Heifetz’s violin, and ran off shouting: “Nothing must happen to this violin!” Heifetz stood in shocked silence for a moment as the man ran off with his instrument. Then he looked at Kaye and burst into laughter. “I guess my violin is more precious than I am!” That broke the tension. Heifetz later told reporters that he saw the soldier put the violin under a truck to try and protect it. “Nobody thought to throw me under a truck,” Heifetz added with a laugh.[8]

Soon the aircraft were gone. As quickly as he had run to take the instrument from Heifetz’s hands, the young soldier was back to return it – apologizing and repeating that nothing must happen to the violin. Heifetz smiled and returned the violin to its case. Then he and the men retreated to a tent for chow. But the day was not over yet. Heifetz and Kaye returned to the truck and drove miles to a local theatre where they played for a packed house of boys just off of the front lines.

Another concert was especially memorable for Kaye. On July 9 they gave an afternoon recital in the Rome Opera House. It was just one month since Allies had taken control of the city. Heifetz played a full recital, opening with the Mozart C Major sonata. After the sonata, Heifetz walked over to Kaye. He had not done this before, and Kaye first thought that he must have done something wrong. But Heifetz leaned down to Kaye and whispered in his ear: “Tonight you are the maestro.” “I tell you, I could hardly go on,” Kaye told us. “My eyes filled with tears.” The last fifteen minutes of the recital were relayed by short-wave to the United States and broadcast nationwide over the NBC radio network.

Wherever they went, Heifetz was greeted by enthusiastic crowds. He always insisted that soldiers not be ordered to hear him. “I don’t want soldiers marched in to hear a concert,” Heifetz told Kaye. “If anybody wants to come and hear me – fine. If not – fine.” But Heifetz had no trouble attracting a crowd. “Those who came were so touched and moved,” Kaye told us. “Don’t forget, this was wartime. You get a piece like Ave Maria, and I don’t care what your religion is, they were putting their lives on the line every moment. You hear a piece like that, and you begin thinking things. There were plenty of tears.” But there was also great joy at hearing Heifetz. “There were a couple of Air Force guys who followed us around! They wanted to know our itinerary. I told them, ‘I don’t even know if I know where we’re going.’” But somehow they found out the schedule and would fly to hear the concerts. They “went all over Italy hearing us play…over and over and over again, which is so astonishing.”

Heifetz was sick for almost two weeks of the tour. On June 30, he awoke with a fever and aching in his legs. He insisted on playing, first at a hospital ward and then at a theatre. The heat was particularly intense, and photographs of the concerts show Heifetz sweating profusely from a combination of the heat and his fever. “Afterwards, Heifetz just wilted,” Kaye wrote. They called a doctor who recommended rest and medication. Heifetz rested much of the next day, but insisted on giving a concert that night against doctor’s orders. “Though weak and having not practiced, Heifetz played the [unaccompanied] Chaconne of Bach in a way I have never heard,” Kaye marveled in his diary, “a monumental, thrilling performance in a scorching hot hall filled with Air Force men. Their attention would shame the most sophisticated Carnegie Hall audience. Just another tribute to Heifetz’s great art.”

For several days, Heifetz pushed on and seemed to rally, but on July 10 he came down with a severe case of the hives. The next day he was even worse. “M.D. came and ordered him to hospital for better care and observation. He couldn’t clutch his fist because fingers and knuckles were so swollen.” For the first time, Heifetz cancelled a concert. The next day he once again violated doctor’s orders and left the hospital. When Kaye saw him enter the hotel where they were staying, he was shocked – Heifetz’s eyes were puffy and his hands and legs were badly swollen.

They cancelled a second day of concerts, and Kaye tended to Heifetz. They played gin rummy that afternoon. Heifetz was frustrated that concerts had to be postponed (he insisted on making them up – and he did). He was also in terrible discomfort from the hives. “He is by nature reserved in the extreme,” Kaye wrote that night. Heifetz seemed embarrassed by his condition, but grateful to Kaye for looking in on him. Heifetz sent Kaye in search of a new doctor the next day. He found one who made some changes in Heifetz’s medication that seemed to help. Heifetz insisted on playing that night – a concert for a large crowd in a tent. It was very successful, but he broke out again right after the concert and Kaye insisted on taking him back to the hospital. The doctor gave him injections that helped to relieve the itching. It was only three days later that he and Kaye experienced the enemy air attack while playing in the war zone.

Despite Heifetz’s illness, and the danger and discomfort of their mission, Heifetz and Kaye asked the War Department to extend their tour of duty. But as Kaye recounted in his diary, the “other mission we requested was turned down by the War Department” because the “area was considered too dangerous.” Shortly before they set off for home on July 24, the two finally had some time off to do some sightseeing. “Brother H and I tried to retain a guide,” Kaye wrote, but guides were hard to come by and the only ones they could find were charging extortionate rates. In the end, Heifetz decided that he would be much better than any guide anyway and insisted on leading the tour. “Result: I had better read the two guide books very carefully to find out where the hell I was,” Kaye wrote that night.

Among their adventures on the tour were several meetings with other famous people. Kaye was thrilled to accompany Heifetz for an audience with the Pope. They also had encounters with entertainment figures who were working for the USO. They had met Marlene Dietrich in Casablanca. After their 4th of July concert in Italy, Heifetz and Kaye visited with Irving Berlin, the movie director William Wyler (whom Heifetz had worked with on his 1939 movie, “They Shall Have Music”), and the actress Madeline Carroll. “We spent hours talking about the future of the world,” Kaye wrote.

Their final concert, on July 23, came as a last minute request from a Navy Chaplain who waited several hours to ask Heifetz to play aboard a battleship stationed nearby. Heifetz agreed. “We had a memorable evening,” Kaye wrote. “Lovely bay with mountain peaks looming in the distance. Their highest points were wrapped in pink clouds. Sun sinking on blue waters – ships all around. The deck was full of sailors – a large number. The piano was so-so but reception marvelous.” After a dinner in the skipper’s quarters, they spent the night talking with Douglas Fairbanks, Jr. It was a fine last day.

At nine o’clock the next morning they took off for home. Back in New York, Heifetz gave an informal press conference about the trip. Asked about how the GI’s liked his playing, Heifetz gave a modest reply: “They were at my concerts, and they didn’t walk out.”[9] And, he added, he gave them a chance to leave if they wanted to: “When I was about to begin a long piece, I often told them that if they wanted to leave, then it would be a good time. They didn’t.”[10] When, in a separate interview, reporters asked Kaye the same question, he was less reticent. He pointed to the surest sign of success: not only did the soldiers not walk out, but they consistently demanded more. At almost every concert Heifetz had to play as many as ten encores.[11]

A little over a month after their return to the United States, Heifetz wrote to Kaye: “I do want to thank you very much for your splendid cooperation during the past tour, for having been such a good and pleasant traveling companion, for your good sportsmanship, and last but not least, for your fine accompaniments and sympathetic support. Am looking forward to some more of it in the near future.” Indeed, Kaye played several times with Heifetz in the coming months. They appeared together on NBC radio’s “Bell Telephone Hour,” gave a recital together in Chicago, and made a series of recordings for Decca in October.

At the end of the recording session, Heifetz once again tested Kaye’s mettle. They had recorded a series of 78 rpm discs, but discovered that they were short one side. Heifetz pulled out a copy of Leopold Godowsky’s Wienerisch and put it on the piano rack. Kaye had never seen the music before, and it has an extremely difficult piano part. Heifetz wanted to record it on the spot. “I can’t do this,” Kaye told Heifetz. But Heifetz, unperturbed, said, “If I didn’t think you could do it, I wouldn’t ask you.” “Well, by golly, we went through it once, and there were some things he corrected, and then we recorded it in one take,” Kaye told us. “That was it! I don’t know how I did it to this day.” But Heifetz was right: Kaye could do it, and he did.

Heifetz still had not reconciled with his long-time accompanist Emanuel Bay, and he asked Kaye to become his new full-time accompanist. Kaye declined, due to family obligations. That was a decision that Kaye later regretted. Heifetz completed the 1944-45 season by making only appearances with orchestra. He was eager to undertake another USO tour in the summer of 1945, so once again he had to find a pianist. Through a friend, Heifetz notified the registrar at the Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia that he needed an accompanist. The registrar put the word out, and Seymour Lipkin, a young 17-year-old pianist, decided to try out. He was a star at Curtis, who had accompanied the school’s director, violinist Efrem Zimbalist (whose usual accompanist, Vladimir Sokoloff, was serving in the military).

Like Heifetz, Zimbalist had studied with Leopold Auer. At a gala Carnegie Hall concert in honor of Auer’s 80th birthday in 1925, Auer, Heifetz, and Zimbalist had played the Vivaldi concerto in F major for three violins, and Heifetz and Zimbalist had played the Bach double concerto (they reprised the second movement on an NBC radio broadcast in 1937). Zimbalist put in a good word for Lipkin, and Heifetz invited him to New York to audition. As with Kaye, they read through a stack of music and Heifetz put Lipkin to the test. Lipkin remembers that one of the pieces that they read through was the Mendelssohn violin concerto. Heifetz took off in the last movement “like a bat out of hell,” Lipkin told us. As with Kaye, he was playing the “catch me if you can” game. “And, I kept up with him,” Lipkin said proudly. Heifetz remained noncommittal at the end of the audition. “I’ll let you know,” he told Lipkin, but then he paused and said with a trace of a smile, “It looks good.” A few days later Heifetz notified Lipkin that he had the job.

Heifetz took Lipkin under his wing. Lipkin was just slightly older than Heifetz had been when he made his U.S. debut, and he took special pains to look after him. “I remember that he was very, very nice,” Lipkin recalls, “and told me exactly what to take, and what kind of chocolate bars I should get, and where I should get them, and how many to get.” And, Lipkin added with a chuckle, Heifetz told him to go to a particular drug store on 57th Street in New York to get a little shaving brush that was especially good for trips. “And I still have it! I still have it, and I still use it. You know, it was pretty expensive – five dollars, or something like that. It was the best, of course. Everything that Heifetz got was the best. And, by god, he was right! It’s sixty years later, and I’m still using it when I go on trips.”

On April 5, 1945, Heifetz and Lipkin boarded a train from New York to Washington, D.C. The next day they boarded an Army plane in Washington and took off for the European Theater of Operations. “I remember it being very uncomfortable,” Lipkin told us. “We sat backwards in bucket seats all the way over.” They stopped at Harmon Field in Stephenville, Newfoundland, a usual layover for those heading overseas. At the air field, Lipkin picked up a flyer that jokingly welcomed transient personnel to “The Riviera of Newfoundland.” With so many military personnel stopping off, the area had developed an infrastructure to house and entertain the troops. Heifetz and Lipkin spent the night. They both had the honorary rank of Captain. “That entitled us to whatever the facilities were for someone of that rank,” Lipkin recalled. So they ate dinner at the officer’s club (known to the locals as the “21 Club”). At 10:00 p.m. they agreed to play an impromptu concert there.

During the course of the evening, the still 17-year-old Lipkin admitted to Heifetz that he had never had a drink. “What??” – Heifetz exclaimed. With a smile and a wink to those around them, Heifetz told Lipkin to sit down. If he was old enough to be a Captain in the U.S. Army, he was old enough to drink. Heifetz ordered a round of gin. “Later they brought out champagne,” Lipkin told us, “so I had some champagne.” He laughed as he recalled that night. “Oh boy, I was so sick!”

From Newfoundland it was on to England, where they learned that President Franklin Delano Roosevelt had died. Heifetz made a special arrangement of God Save the King to play at concerts in England. He also made an arrangement of La Marseillaise to play in France, and he brought along his arrangement of The Star Spangled Banner. From England, Heifetz and Lipkin proceeded on to France and then to occupied Germany.

As in Italy, Heifetz played near the front. On one occasion, the jeep carrying Heifetz and Lipkin got lost and they found themselves behind enemy lines. On another, there was an air raid and they had to scramble under the stage for cover. This time, Heifetz had brought his priceless Guarnerius on the tour, and Lipkin remembers him clutching it during the air raid. Heifetz liked playing near the front line. “My most attentive and appreciative audiences were those just in from the front – all muddy and wet, faces grimy, with their rifles and gear on their backs,” he told the New York Times upon his return to the U.S. “One soldier came up to me after a concert to say that he had never been to a concert before, but added that if what he heard was good music, he was all for it. They seemed unable to hear enough good music.”[12]

Throughout the tour, Heifetz refused to accept the small daily honorarium that the government paid those who toured for the USO. “We were paid ten dollars a day, or something like that,” Lipkin told us. “That was standard. But Heifetz refused to take it.” The military bureaucracy had a fit because now they couldn’t balance the books. “They said: ‘Look, please, Mr. Heifetz. Just take it. Do you mind?’” But for Heifetz, it was a matter or principle and he would not back down. “He absolutely refused to take the money,” Lipkin said with a laugh. He didn’t care if it made life difficult for the bureaucrats. “He wouldn’t accept it! That was really funny.”

By the time Heifetz and Lipkin arrived in Europe, the war was almost over. In March, Allied forces had crossed the Rhine. On April 21, Heifetz and Lipkin played for the Fifteenth Army which, together with the U.S. Ninth and First Armies had encircled the Ruhr and taken more than 325,000 German prisoners. Photographs after the concert show Heifetz and the others to be in high spirits. The Soviet Army had begun its final drive on Berlin on April 17, and everyone knew that Allied victory over Germany was near. Adolf Hitler committed suicide on April 30 and two days later German resistance in Berlin ended. Germany unconditionally surrendered on May 7. May 8 was celebrated as “Victory in Europe Day.”

Lipkin and Heifetz were in Beckum, Germany when the war ended and they gave a VE-Day concert there at the liberated “Deli Theater.” Afterwards, Heifetz was mobbed by GIs who asked for his autograph on captured German marks. One was a sergeant who absolutely adored Heifetz and clearly knew something about music. He told Heifetz that he had saved a salami for a special occasion. This was wartime, and salami was a tremendous treat. Would Heifetz and Lipkin share it with him? They agreed. “We must have driven 60 miles to spend VE-Day with that sergeant and to break open that salami,” Lipkin told us with a big laugh.

Just over a week later, General Omar Bradley asked Heifetz to perform as part of a banquet lunch honoring the Russian general Marshal Ivan Koniev, Commander of the First Ukrainian Army Group. Bradley was returning the favor of an earlier meal that Koniev had hosted in his honor. After Koniev’s lavish banquet, a chorus of Red Army soldiers gave a resonant rendition of The Star Spangled Banner. Then a phenomenal ballet troupe burst into the room and began dancing to the accompaniment of a dozen balalaikas. Bradley was quite overwhelmed. “Splendid!” he exclaimed to Koniev, who nonchalantly shrugged his shoulders and said, “Just a few girls from the Red Army.”

Bradley wanted to outdo Koniev, so he recruited not only Heifetz, but the actor Mickey Rooney, and the Glenn Miller Band to perform at the banquet he hosted for Koniev at his headquarters in the German spa town of Bad Wildungen, about 70 miles north of Frankfurt. The Russians arrived by transport planes shortly before the luncheon and were taken by a fleet of Cadillacs to the Banquet Hall in the Hotel Fürstenhof. After a long meal and many toasts, the entertainment began. Heifetz and Lipkin appeared first, dressed in khaki uniforms. They played five selections, starting with Heifetz’s arrangement of the Negro spiritual Deep River and ending with Prokofiev’s March (from “The Love of Three Oranges”).” This time it was Koniev who was overwhelmed. “Magnificent!” he exclaimed in delight. “Oh that,” Bradley replied nonchalantly. “Nothing, nothing at all. Just one of our American soldiers.”[13]

Like everyone, Heifetz was in excellent spirits. He posed for photographs with band members in the courtyard of the hotel, and agreed to participate in a spur of the moment concert that night for some 3,000 troops from Bradley’s Twelfth U.S. Army Group. The concert took place outdoors, in an amphitheatre normally used for concerts by the hotel orchestra. The Glenn Miller Band played first. Then they moved to the back of the stage, and Heifetz and Lipkin began a series of solos.

After about two numbers, rain began to pour. The stage was partially covered, so Heifetz managed to stay dry, but the soldiers were getting soaked. “Well fellows,” he announced, “it looks like we better stop.” David Sackson was a violinist in the Glenn Miller Band and was sitting on the stage that night. “They yelled and screamed and wouldn’t let him go,” Sackson told us. Heifetz played another number. Again, the soldiers demanded more. Heifetz ended up playing a full recital. “So, what does this tell you?” Sackson asked. “It tells you that there was something magical about the guy’s playing!” With the rain, the soldiers had the perfect excuse to leave. But Heifetz’s playing captivated them. This, and countless other examples of enthusiastic audiences among the troops, reinforced Heifetz’s belief that it was wrong to play down to audiences. “Soldiers are very particular about the quality of their entertainment,” he said. “When the subject is music, the better it is and the more sincerely it is performed, the better they like it. The superficial is immediately detected and disdained.”[14]

In the coming weeks, Heifetz and Lipkin toured throughout Germany and France. Heifetz’s mood was mostly ebullient. Photos show him washing dishes with the troops, helping to build a wooden platform, marching along a muddy road in Germany, and proudly driving a military jeep. The high spirits were dampened only by the news of the liberated concentration camps and the plight of those who had been imprisoned and killed there. Heifetz, a Jew, did not speak much about this to Lipkin, but he was clearly disturbed by the news. Lipkin remembers that Heifetz was reading a book about Zionism during their tour. Two years earlier Heifetz had been asked what piece he would like to play to celebrate the defeat of Hitler. Rather than playing a jubilatory piece, Heifetz said he would like to play the lament Hebrew Melody by Joseph Achron.[15] He did just that on VE-Day. After his appearances for the troops in 1945, Heifetz never again played in Germany.

Everywhere they went, Heifetz and Lipkin played for large and enthusiastic crowds. Photos of an outdoor concert in Calas, France on June 17 showed soldiers almost as far as the eye could see. Among their last appearances before returning to the United States on June 29 were two recitals at the Palais de Chaillot in Paris on June 11 and June 14. Among those who attended was a young violinist named Marx Pales, who later went on to conduct the Huntsville Symphony in Alabama.

The Palais de Chaillot was an impressive structure. It overlooked magnificent fountains and the Eiffel Tower. Pales attended both of the concerts that Heifetz gave there. “Heifetz and Lipkin were dressed in olive-drab uniforms and Heifetz announced each selection,” he told us many years later. “At the conclusion of the program, Heifetz asked the audience what encores they would like to hear.” As usual, the one that they requested both nights was the Hora Staccato. “Alright then,” Heifetz said as he introduced the piece. “I shall play for you the ‘Horrible Staccato.’” “His down and up bow staccato was dazzling,” Pales remembered with awe.

After the second concert, Pales drew up the courage to meet Heifetz. “I found my way to his dressing room where a crowd had already gathered and a U.S. Army captain stood by. Heifetz was most gracious talking and signing autographs.” Meeting with these men who had sacrificed so much, meant a great deal to Heifetz. After awhile, the Army captain approached him and said in a loud voice: “Mr. Heifetz, we need to leave now. The general is waiting.” There was still a long line of soldiers waiting to meet him, and Heifetz’s reply summed up his feeling about the troops and his sense of responsibility to them. Heifetz looked up at the soldiers waiting in line and flashed them a smile. Then he turned to the captain and said just what all of the soldiers wanted to hear: “I’m sorry, Captain, but you can tell the general that he will have to wait.”

John Maltese was professor emeritus of music at Jacksonville State University, Alabama. John Anthony Maltese is the Albert B. Saye Professor and Head of the Political Science Department at the University of Georgia, and he is currently writing the authorized biography of Jascha Heifetz.

This article originally appeared in abridged form in The Strad Magazine, and is reproduced here with their permission.

[1] Unless otherwise indicated the quotes in this article are from the authors’ personal interviews with Milton Kaye, Seymour Lipkin, Marx Pales, and David Sackson, and from Milton Kaye’s diary entries during the 1944 tour. Other background information is drawn from the authors’ interviews with Jack Benny and Daniel Mason.

[2] Ayke Agus, Heifetz as I Knew Him (Portland, Oregon: Amadeus Press, 2001), pp. 128-30.

[3] Radio broadcast, October 18, 1941, “Radio America Preferred,” broadcast from KHJ, Hollywood, California.

[4] T.R. Kennedy, Jr., “Heifetz Views the Radio,” New York Times, 22 July 1945, p. 45.

[5] Kennedy, “Heifetz Views the Radio,” p. 45.

[6] “Heifetz Tours Front To Play for G.I. Joe,” Christian Science Monitor, June 12, 1944, p. 1.

[7] Quoted in: Michel Mok, “Only Mad People Go Out and Steal Strads,” New York Post (December 13, 1937), p. 15.

[8] Heifetz quotes from “Heifetz Fiddled, But Neither Rome Nor G.I.’s Burned,” Washington Post, August 7, 1944, p. 6.

[9] “Heifetz, Home, Says GI’s Are 70% for Fine Music,” New York Times, August 5, 1944, p. 4.

[10] “Heifetz Fiddled, But Neither Rome Nor G.I.’s Burned,” Washington Post, August 7, 1944, p. 6.

[11] “In the World of Music,” New York Times, August 6, 1944, p. X4.

[12] T.R. Kennedy, Jr., “Heifetz Views the Radio,” New York Times, July 22, 1945, p. 45.

[13] Omar N. Bradley, A Soldier’s Story, p. 553.

[14] Kennedy, “Heifetz Views the Radio,” p. 45.

[15] Marjorie Kelly, “What Music for ‘Victory Day?’” Washington Post, July 25, 1943, p. L3.